New Jersey’s Environmental Justice Law: A Potential Model for EJ National Focus

A version of this article appeared in a recent issue of EM Magazine, a publication of the Air & Waste Management Association. This is a more comprehensive update to a topic discussed in the May 2021 issue of the CDRA e-Newsletter.

By Chris Whitehead

New Jersey’s Environmental Justice Law is being lauded as one of the most comprehensive in the United States and is being considered as a potential national model. The Garden State enacted the law (the EJ Law) in September 2020, empowering the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) to deny permits for certain facilities if the facility would contribute to a disproportionate impact on an overburdened community (i.e., a community where environmental justice concerns are present). The law contains a strong framework for addressing environmental justice issues during permitting of facilities, but several complicated issues need to be considered before the law is implemented, and before it truly can serve as a model for other jurisdictions.

Overview

There has been a growing discussion regarding the siting of facilities with significant environmental impacts in low-income, typically urban communities. According to the NJDEP and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), environmental justice efforts respond to this discussion by ensuring “fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” {1} However, environmental justice implicates more than just the siting of facilities. In fact, environmental justice has been in the national spotlight in recent years because of specific environmental crises, including the Flint water crisis, where public drinking water was polluted with lead and other contaminants, and because of legacy contamination in the vicinity of these communities; in fact, it has been reported recently that 70 percent of sites on the National Priorities List under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (i.e., Superfund Sites) are located within one mile of federally assisted housing. {2}

The EJ Law addresses this discussion by incorporating environmental justice into the permitting process for certain permit applications. The requirements of the law apply to covered facilities, seeking applicable permits, located in an overburdened community.

- Covered facilities include: All major sources of air pollution (i.e., facilities with Title V air permit, such as power plants), solid waste facilities, landfills, incinerators, sludge processing plants, sewage treatment facilities that process more than 50 million gallons per day, scrap facilities, as well as recycling facilities that process more than 100 tons per day.

- Applicable permits includes “any individual permit, registration, or license” issued under numerous New Jersey environment laws. Notably, the definition only explicitly includes individual permits, which contain requirements specific to the individual facility; the definition may not include general permits, permits-by-rule, or other standardized permits. While the legislation applies to all covered permits for a new facility or for the expansion of an existing facility, it only applies to the renewal of a Title V permit, not the renewal of any other covered permits.

Overburdened community is based on certain socio-economic demographics —Any census block group, as determined in accordance with the most recent US Census, in which:

- at least 35 percent of the households qualify as low-income households; OR

- at least 40 percent of the residents identify as minority or as members of a State recognized tribal community; OR

- at least 40 percent of the households have limited English proficiency.

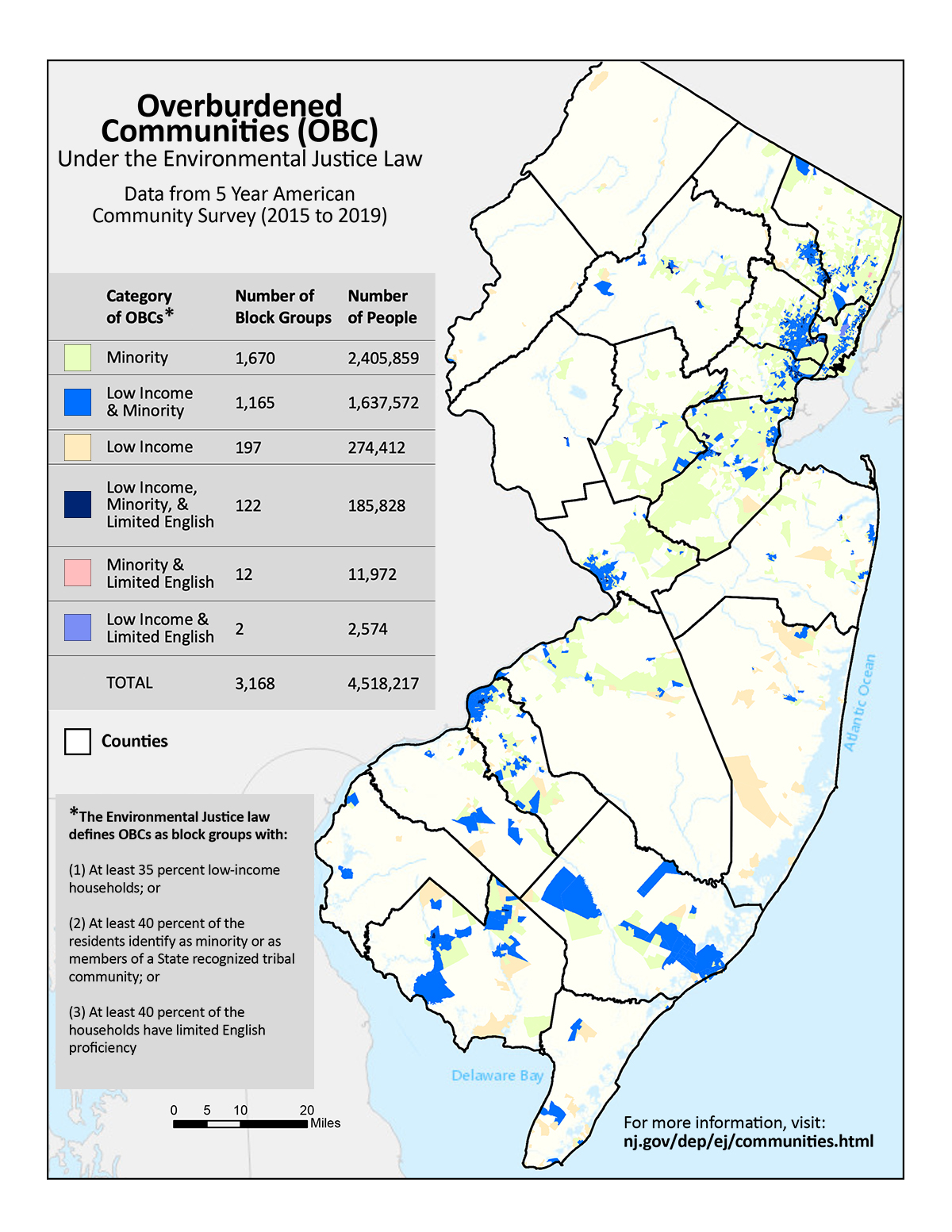

According to NJ Spotlight, “the . . . definition of ‘overburdened communities’ could apply to more than 300 municipalities and over 4 million residents.” New Jersey has released several tools to identify and map overburdened communities, including the GIS mapping tool highlighted in Figure 1

Figure 1

If these three conditions are met, the facility must comply with the EJ law, which the NJDEP recently described as possibly involving a multi-step process.

- Step 1 – Initial Screen: The NJDEP expects to provide a data mapping tool that is to be publicly available and can be used to determine whether the overburdened community in which the subject facility is or will be located already is subject to disproportionate environmental and public health stressor levels when compared to the appropriate geographic point of comparison.

- Step 2 – Disproportionate Impact Analysis: Through the preparation of an Environmental Justice Impact Statement (EJIS), including a public hearing in the host community, the subject facility analyzes whether and how the proposed facility will cause or contribute to disproportionate stressor levels and proposes avoidance measures. If the subject facility cannot avoid causing or contributing a disproportionate impact, it is subject to the substantive requirements of the EJ Law referenced above and discussed in the next steps.

- Step 3 – Permit Conditions (Applicable to Facility Expansions and Title V Renewals): If an existing facility has a disproportionate impact, where necessary to avoid or minimize potential adverse impacts, NJDEP may impose binding permit conditions concerning the construction and operation of the facility.

- Step 4 – Denial or Compelling Public Interest (Applicable to New Facilities): If a new facility projects that it will have a disproportionate impact, the NJDEP must deny the permit application unless the new facility will serve a compelling public interest in the community where it is to be located. If so, the NJDEP may impose binding permit conditions on the construction and operation of the facility to protect public health.

Evaluation of Specific Issues

The EJ Law does not take effect until the NJDEP enacts regulations to implement the law, and NJDEP must resolve several significant issues in these pending regulations.

- EJIS Components: NJDEP will use the EJIS to determine the cumulative impact of the project, whether the project has a disproportionate impact on the host community, and, if it does, whether to grant or deny the permit, or impose conditions. However, the EJ Law does not explicitly define the specific components of the EJIS, or the environmental impacts to be considered. To support the EJIS, the NJDEP intends to rely as much as possible on existing data sets, although some modelling and/or forecasting is expected, especially with respect to air emissions. The NJDEP also noted that it might allow facilities to prepare a single EJIS for separate permits, even if these permits are to be obtained at different times. As a final matter, during a stakeholder meeting there was debate as to whether greenhouse gas emissions would be evaluated through EJIS because these emissions don’t always have direct, discrete environmental impacts on individual communities and, instead, have more global/regional impacts.

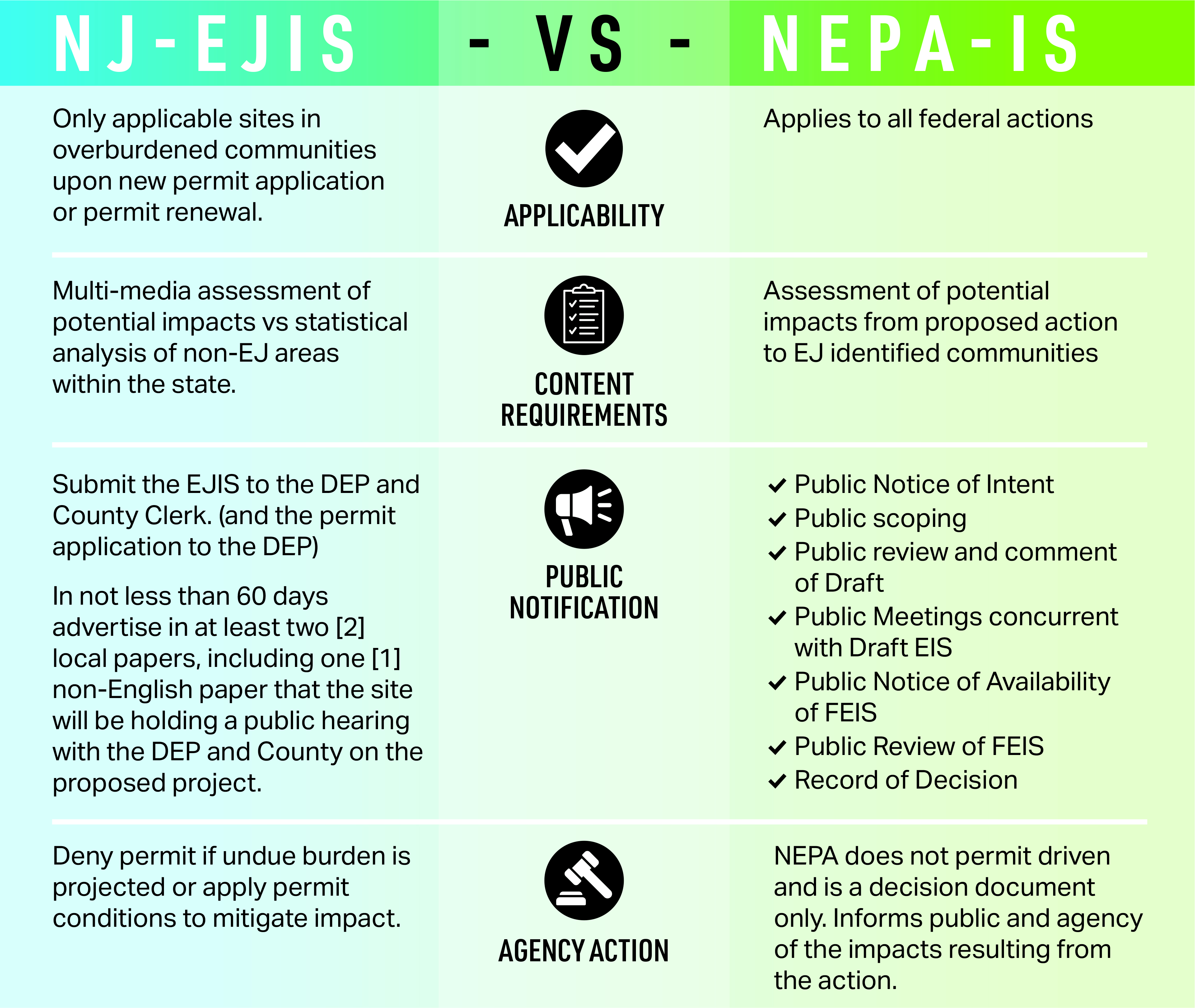

- Differences between EJIS and Environmental Impact Statement: The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and recent Executive Orders from President Biden {3}, require all federal agencies and operations on federal land to prepare an environmental impact statement, which is to consider environmental justice impacts. Some of the main differences between the NEPA EIS process and the EJIS process are detailed in Figure 2. Two key points to remember are that: (i) the NEPA process does not directly result in a permit, and (ii) an EJIS is only required for applicable facilities within an overburdened community while all federal agencies develop implementation guidelines to adhere to NEPA.

Figure 2

- Determination of Disproportionate Impact: Once an EJIS has been prepared and the cumulative impact of the project determined, the next step would be to determine whether the project has a disproportionate impact on the host community. The disproportionate impact analysis involves comparing the host community to another community, and the EJ Law simply directs NJDEP to compare the impacts on the host community to “those borne by other communities within the State, county or other geographic unit of comparison” without further guidance. In a stakeholder meeting on the subject, NJDEP representatives discussed several approaches for determining the appropriate geographic unit of comparison through a statistical approach based on widespread impacts. For instance, one approach considered whether the host community had more air pollution than a specified percentage of other communities within the State. Another approach compared the host community statistically to other communities within the same county. Yet another approach compared the host community to communities with the same county as well as the State. Each of these approaches involves certain priorities and trade-offs. In the end, the NJDEP representatives said they would select one of these approaches to be applied uniformly across all sites and impacts, which would provide additional certainty to the process but would curtail the ability of permittees and communities to identify case-specific factors. However, the NJDEP representatives did not explain how the disproportionate impact analysis would address different impacts, as well as other obvious nuances.

- Scope of NJDEP Authority to Impose Permit Conditions: If a project would have a disproportionate impact, it may still proceed in certain instances subject to conditions imposed by the NJDEP. The law states that permit conditions are to be imposed “on the construction and operation of the facility to protect public health” and are intended “to avoid or reduce the adverse environmental or public health stressors affecting the overburdened community.” Federal case law suggests that permit conditions must demonstrate a “nexus” and “rough proportionality” between the conditions being imposed and the environmental impact. There must be a direct connection between the harm caused by the facility and the condition being imposed, which must be similar in size and nature to the harm. Related questions include: Are facilities automatically required to make all possible reductions of environmental impacts before conditions are considered? Can the NJDEP impose a condition that provides one type of environmental benefit (i.e., to improve air quality) to mitigate/offset an impact of another type (i.e., water pollution)? While NJDEP has indicated that monetary burden will not be an acceptable argument to avoid these permit conditions, it must be considered under existing case law to evaluate the proportionality of the conditions. In a recent stakeholder discussion, NJDEP noted that mitigation may be allowed, but advised that there will be limits on the scope of mitigation and how it will impact the process.

- Considerations for Facilities with Significant Air Emissions: The 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments enacted provisions to include streamlined permitting through what is now commonly referred to as Title V air permit. If a facility has a potential to emit above major source thresholds they must obtain a Title V permit and adhere to various compliance conditions. Facilities with Title V permits are one of the largest groups subject to the EJ Law, and NJDEP informally confirmed that about half of such permits are within overburdened communities. Existing facilities with Title V permits are familiar with strenuous monitoring, testing, reporting, and control requirements. State agencies often implement their own targeted regulations to address specific air issues, such as hazardous air pollutant (HAP) risk reduction. As noted above, the EJIS evaluates the environmental and public health impacts associated with a facility, including air emissions. The NJDEP recently updated their Risk Screening Worksheet (RSW) and revised downward many HAP reporting thresholds. The RSW process provides a useful starting point for air impact examinations, because it establishes pollutant thresholds based on the risks associated with environmental and public health impacts. There is also the question of how facilities that do not produce HAP emissions will proceed. If HAP-emitting facilities are provided with gating criteria, the same consideration should be expected for facilities that only emit criteria pollutants (such as nitrogen oxides or particulate matter). If a facility potentially has high air impacts, of either criteria pollutants or HAPs, it should consider conducting air dispersion modeling and risk assessments in order to establish their emissions do not substantially impact the surrounding community.

While the EJ Law is garnering a great deal of attention for its scope and potential impacts, care must be taken with the implementation regulations to provide a clear framework for affected facilities. These regulations are expected at the earliest in late 2021. The NJDEP is continuing the stakeholder process on this transformational regulation — the authors of this article will continue to watch for developments.

Sources

[1] https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/learn-about-environmental-justice#:~:text=Environmental%20justice%20(EJ)%20is%20the,environmental%20laws%2C%20regulations%20and%20policies.

https://www.nj.gov/dep/ej/docs/ej-pres-20201022.pdf

[2] https://www.povertylaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/environmental_justice_report_final-rev2.pdf

[3] Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis. Executive Order 139900 of January 20, 2021 and Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad. Executive Order 14008 of January 27, 2021.